By Robert Richter, Caleb Richter-Tate, Isaac Murillo Olmeda

Abstract: The growing body of archeological evidence defining West Mexico’s coastal pre-Hispanic geography and cultures points to the San Blas/Matanchen Bay area as a nexus of early and prolonged settlement and cultural development with a uniqueness and depth distinct from the empires of the central plateau and southern Mexico. In addition, two indigenous groups, the Aztecs and the Huichols (Wixárika), have origin narratives with direct association to the San Blas/Matanchen area and to the psychic and spiritual space within a larger Mesoamerican historical tapestry. Recent explorations in the San Blas area, revealing evidence of human construction on a monumental scale with geographical and astronomical alignments, underscore the possibility that this region had significant population, high levels of social organization, and was a major cultural center earlier than previously estimated. Discoveries suggest that contemporary concepts of chronologies of development and the diasporas of peoples throughout Mesoamerica may have to be reconsidered.

key words: Nayarit, Aztlan, San Blas, Huichol, Wixárika, Aztecs, Boturini Codex, pyramids, Mesoamerican origin narratives

The Historical/Geographical Background

In recent decades, more focused exploration has taken place by both American and Mexican professionals on Mexico’s west coast, and the cultural layers they are beginning to reveal is making this region’s pre-Hispanic past more appreciated for its own depth and uniqueness, rather than as some sub-cultural spin-off of the Mesoamerican cultures of the central plateau, namely Teotihuacán, Tula, and the Aztec and Mayan Empires (Mountjoy 2000; Beekman 2010; Garduño Ambriz 2015). As more individual sites are explored and catalogued, and old sites are re-examined at new levels of detail, a clearer overview of the region’s cultural-historical character, chronologies of development, and intra-regional relationships over four millennia is being puzzled out (Meighan 1974; Williams 2004; Beekman 2010; Mountjoy 2015, Mountjoy 2000).

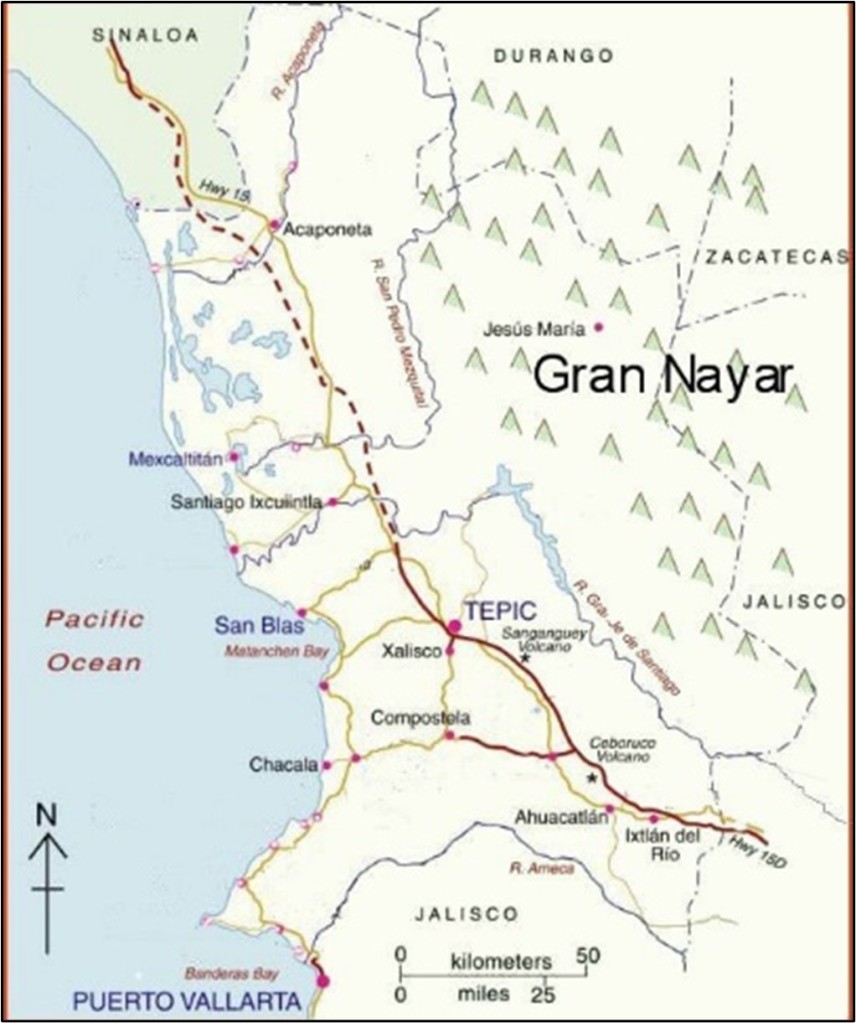

West Mexico as a distinct cultural region of its own was first delineated by Sauer and Brand in 1932, as an area defined by the “Río Grande de Santiago at the south, that of Culiacán at the north and the country between,” (Sauer and Brand 1932: 4) that is, southern Sinaloa and northern Nayarit. By 2010, this cultural region had come to include all of coastal Nayarit, Jalisco, and Colima, as well as parts of Michoacán, Zacatecas, and Guerrero, (Beekman 2010) where archeological researchers continue to find general similarities in tomb and temple architecture, relic finds, and pottery styles that suggest continued habitation and connection (Beekman 2010). Yet little has been found within the region to define it as a unified cultural complex, and a sense of “sub-regions” has developed with, once again, the coastal plain of Sinaloa, Nayarit, and Colima considered a distinct area with its own archeological characteristics and identifiable cultural traits. J.B. Mountjoy, who has done the most work in Nayarit, defines the southern half of the area as encompassing the “coastal plain and adjacent foothills from the Río Santiago in central Nayarit on the north, to the Río Balsas on the south at the border of Michoacán and Guerrero (Mountjoy, 2000: 81).

Separating the southern from the northern part of this coastal plain is the Mexican Volcanic Axis. This refers to an east-west mountain range that begins at San Blas on the west coast, where sierras first meet the sea, and runs to the Gulf of Mexico on the east. To its north, the geography is mostly desert with easier ocean transport along the widening coastal plain of lagoons and estuaries. To the south, two-season tropical Sierra Madre crowd the Pacific, a rugged coast with bays and rain-fed rivers, making ancient navigation difficult. Archeology in the northern area generally has centered on various substrata of the Aztatlan Cultural Complex, which evolved from circa 200 A.D. and existed in some form on the coastal plain until The Conquest. Research to the south traces the gradual northly spread of earlier, possibly pre-Olmec-related, Capacha and Opeño cultures from Guerrero and Michoacán (Mountjoy 2000), working out possible chronologies of development and spread mostly through pottery shard comparisons and architectural similarities.

Within this continuing discussion of geographical definitions, the identification of cultural complexes, and their possible chronologies and relationships, the growing body of comparable archeological evidence comes from a variety of individual sites scattered throughout a broad geography. Each has a particular body of identifiable cultural traits and characteristics determined to be from some vague era of a few centuries on a timeline three thousand years long. Only one small area of coastal west Mexico yields not only carbon-dated evidence of the earliest human occupation on the coast, but evidence of continuous occupation and evolvement through several layers of cultural identity, development, and chronology (Mountjoy 1971; Mountjoy, Taylor, and Feldman 1972; Mountjoy and Claassen 2005; Mountjoy 2015) from the Late Archaic epoch with the Matanchen Complex (2200 B.C.–1730 B.C.) to the Late Post-Classic epoch and the last phases of the Late Aztatlán Complex near Santiago Ixquintla (1350 A.D.-1530 A.D.).

The concentrated archeological record of this geographic area, defined in this article by the Río Grande de Santiago on the north and the village of Zacualpán, Nayarit, and its agricultural floodplain fifty miles to the south, with at least “five major archeological complexes in between” (Meighan 1974; Mountjoy 1971; Scott and Foster 2000: 134) suggests the area deserves a fresh assessment as a major long-standing and continuously evolving cultural nexus on the Mesoamerican historical timeline, worthy of more focused exploration, anthropological study, and cultural preservation. Especially when two other major interdisciplinary factors, geographical and historical, emphatically reinforce this call, and those factors are the subject of this article.

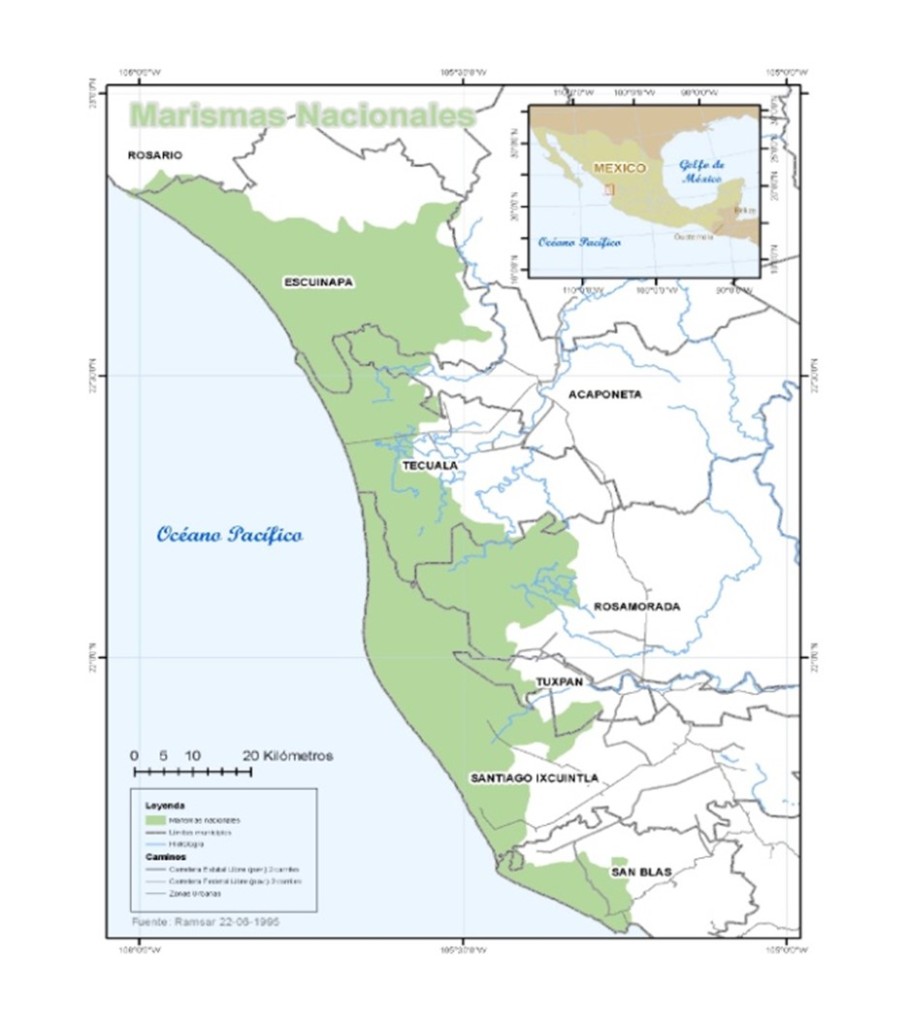

Even in the twenty-first century, the Nayarit coast around San Blas and Matanchen Bay is a dynamic and powerful region, geographically, ecologically, environmentally, and culturally. Here, three eco-systems clash and coalesce, and the surrounding environment offers a wealth of natural resources in a harsh and rugged topography. In this unique region, a vortex of natural abundance and variety in minerals, flora, and fauna, exists and has provided habitat, resources, and food from land and sea for human development for at least 4000 years. The coastal lowlands that stretch from Río Santiago north 140 miles toward Mazatlán and the Tropic of Cancer, a dense swampland of insects, reptiles, and birdlife, are now protected as the Marismas Nacionales Nayarit. This marshy region of mangrove lagoons evolved over several millennia into the spawning bed of shrimp and other crustaceans that provide the lowest part of the food chain in the seawaters where the deep, cold southern Pacific currents and the shallow, warm Sea of Cortez meet on the Nayarit coast. North of Río Santiago, two rivers, Río San Pedro and Río Acaponeta, and at least ten others identified by Carl Sauer, have taken the watershed run-off of the Sierras from northern Nayarit, central Durango, and Sinaloa, spilling their eroding waters into the Pacific, and continually changing the coastal geography to the south (Sauer and Brand 1932) as late as the mid-twentieth century. The short coastal strip from the mouth of Río Santiago to the southern tip of Matanchen Bay may not have even existed four thousand years ago, certainly not in the form that it does today. The earliest Spanish maps of the coast show a quite different coastal shape than exists today, and they are relatively new maps (Garagito 1766; Pantoja 1775; Pantoja y Arriaga 1885 in Cartografía 1984). The construction of dams on most of these rivers–five on Río Grande de Santiago alone since 1955–has nearly stopped completely the deltaic, alluvial flows of sediments from the Sierra Madres into the Sea of Cortez and down the Nayarit coast. Since 2005, the coastline has changed little, reaching an “equilibrium state,” (Martinez Martinez, Silva y Mendoza 2014: 99) but prior to that, the Nayarit coast changed continually, including Matanchen Bay. Sauer adds that the

“most significant major event is found in warping of the land…great flood plains coalesce and develop between them freshwater lakes…tidal flats, marshes, and lagoons extend almost to the base of the mountains…The whole southern section is amphibious land…This fact, together with the submerged shelf on which the Tres Marias Islands lie to the west, suggests that this is a subsiding area, little better than kept awash by the great deltaic accumulations which it receives.” (Sauer and Brand 1932:13)

Simply inferred from this geographical evolution is that any signs of civilization earlier than the Aztatlán Complex built on the changing alluvial coastal plain thousands of years prior is either buried under the deltaic flows or under the seabed. In fact, the coast itself looked dramatically different four thousand years ago. Accompanying maps show the Nayarit coast today and what it might have looked like four millennia ago.

Nayarit coast, 1500 B.C.

As Sauer describes flood plains farther north, “The isolated cerros and hill clusters that stand above the plain were islands, as is shown by the beveled summit, benches, and cobble veneer,” (Sauer and Brand 1932: 12). In the San Blas area, the Lighthouse Hill, reduced by half in the 1980s to construct a levee; Cerro de Basilio (the contaduría)–at its northeast base are remains of stone terraces meant for houses dating back to the Middle Formative epoch (950 B.C.-335 B.C.); Cerboruco, a small hill a few hundred meters to the south on the northwest cusp of Matanchen Bay; Chacalilla, a pre-Aztatlan village on a hill northeast of San Blas; and Zacualpán, another pre-Aztatlan site, may have all have been islands 4,000 years ago. The islands of Aztlán?

The Origin Narratives

At least two different indigenous groups have origin narratives, called myth, legend, and symbolic representation in contemporary academic jargon, that connect directly, geographically, with this stretch of southern Nayarit coast. One of those groups is the Aztecs. Aztlán, first of all, is NOT AzTATlan, the cultural complex defined by Sauer. Aztlán is, most academics insist, a mythological place, the place of origin for the Mexica people, those who became the Aztecs and eventually built the most magnificent city in the pre-Columbian world on a lake of floating islands, Tenochtitlán, buried now under Mexico City (Matos Moctezuma1990). To claim roots of origin in Aztlán was to proclaim authenticity and heritage as old as the gods and the land itself. That origin bestowed on the citizens of Tenochtitlán, at least in their own minds, entitlement to empirical rule and riches and to be chosen enforcers and benefactors of the will of the gods.[i]

Aztlán translates from Nahuatl, language of the Aztecs, as “Place of Herons,” and since their ancestors’ departure from there more than four centuries before they had built their great empire, its “real” location was forgotten. All that was known was that Aztlán was northwest of Mexico’s central plateau and the Aztec capital, beyond the desert lands of barbarians called “the Chichimecs.” Closely tied to this environment, this place of herons, was Chicomoztoc, known as being a place of “seven caves on seven islands.” (Leven Rojo 2014) In some versions of the Mexica migration story, they are one and the same place, but Chicomoztoc may have been only a part of Aztlán, a barrio, a borough, an older and sacred quarter. Both were revered as the ancient homeland of the Aztecs, and when Moctezuma Ilhuecamina sent priests to rediscover Chicomoztoc, its location lost through the intervening centuries, they discovered a “big hill in the middle of water (where) there were some mouths of caves or cavities” (Schávelzon 1978: 158; Matos Moctezuma 1990).The developing environment of the central Nayarit coast over millennia fits the description of “a place of herons,” and a place of “seven caves on seven islands.” It is an ecosystem for herons, egrets, and other aquatic birdlife, the lowland tidal swamps and saltwater mangrove marshes of the Marismas Nacionales Nayarit.

1 Historians summarize the Aztecs’ origin and migration story in various ways. Besides origin accounts narrated to friars who recorded them into their journals and histories, the story is the subject of many “codices,” which are pictoglyphic accounts in various book forms. See Arias de Sabedra, A. (899; Beekman and Christensen 2003; Ortíz García, E. (1997); Navarette, F. (2000); Campos Moreno, A. 2016; Smith 84.

A contemporary historian says that images of Aztlán were similar to those of Teotihuacan, that temples existed there. Another, earlier historiographer, Alva Ixlilóchitl, places Aztlán toward the west and beyond Jalisco, and only Nayarit and the Tres Marias Islands are north and west of Jalisco. A native archeologist and former governor of Nayarit, Wigoberto Jiménez Moreno, suggested Mexcaltitan, a centuries-old village on a two-acre island in the lower Río Grande de Santiago as the “place of herons,” Aztlán (Leben Rojo 2014), as does Friar Duran in his History of the Indies of New Spain (1581). Friar Antonia Tello’s indigenous sources relate in a “mix of reality and fiction” (Campos Moreno 2016: 13) the Aztec migration story similar to Duran’s in his Crónica Miscelanéa (1653), saying the Mexica left Aztlán and went to Chicomoztoc where they dwelled for ten years, raising corn and making sacrifices of the locals (Tello 1891). Finally, the archaeologist Carl Sauer, the earliest explorer who gave the Aztatlan culture its name, rejected the idea of Aztlán existing as far north as Sinaloa, stating in his 1932 ground-breaking work that the Aztatlan culture was pre-Aztec and at most an outpost of the culture on its northern fringe (Sauer and Brand 1932).

Modern Mexcaltitan in the Río San Pedro, but around 500 years old,

the village is too young to have been “Aztlán.”

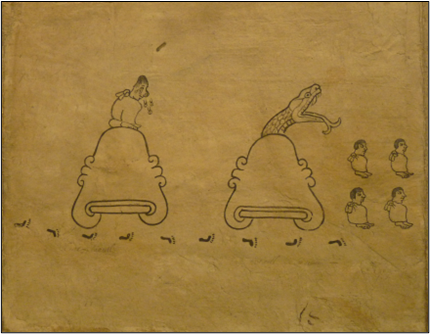

Nearly all contemporary anthropologists adamantly insist that Aztlán was never a real, physical place, but “a manner of speaking,” that it belongs to mythic, sacred space, and only “corresponds” to centuries of Chichimec migrations from their mythic northwest origins which eventually ended on the muddy shores of Lake Texcoco and their transformation into Aztecs with the most beautiful metropolis in the world (Meyer 1997). Yet, besides the early colonial sources relating the origin of the last Mexica migration (Tello and Duran), several indigenous copies of pre-Columbian codices depict in pictographs the origin and route in this migration history. They are considered invaluable sources for understanding the culture and history of the pre-Columbian peoples. One of the most famous, the Borturini Codex, now lodged in the National Museum of Anthropology, consists of twenty-two panels sewn together into a folding booklet. Scholars have geographically identified nineteen actual sites along the migration route from Aztlan to Tenochtitlan on sixteen of the pictographs (Gutiérrez de MacGregor and Gonzalez Sánchez 2011, 43-44). On the first five panels, Aztlán, Teoculhuacan, Tomoanchan, Cuextecatlichocayan, and Coatlicamac remain unlocated geographically, “because they have been lost over time, or there is not sufficient information to locate them in a precise manner,” (Gutiérrez de MacGregor and Gonzalez Sánchez 2011, 38). To maintain that these are mythic places only, with no direct geographic connection to the earth because they cannot be located, is simply in contradiction to the rest of the codex itself. Recent explorations in the San Blas area have raised the argument that panel five of the Boturini Codex in particular, depicting two sacred hills or pyramids side by side–the unlocated Cuextecatlichocayan, and Coatlicamac, may also be associated with actual geographic features.

Cerritos/pyramids near San Blas, Nay., view from the north.

Panel 5 of the Boturini Codex.

A debate about the physical existence of Aztlán is not over. One scholar has shown that “Aztlan migration chronicles… in fact preserve valid historical information on population movements in Postclassic central Mexico” (Smith 1984). Using Nahuatl and Otomí narratives as well as linguistic and archeological analyses, he has worked out arrival dates for different waves of migration from the northwest to the central basin of Mexico, listing these groups as Chichimecs– non-nahuatl speakers, and three groups of nahuatl speakers from Aztlán, with the Mexica being the last to arrive. Aztlán as a geographical locale cannot be ruled out.

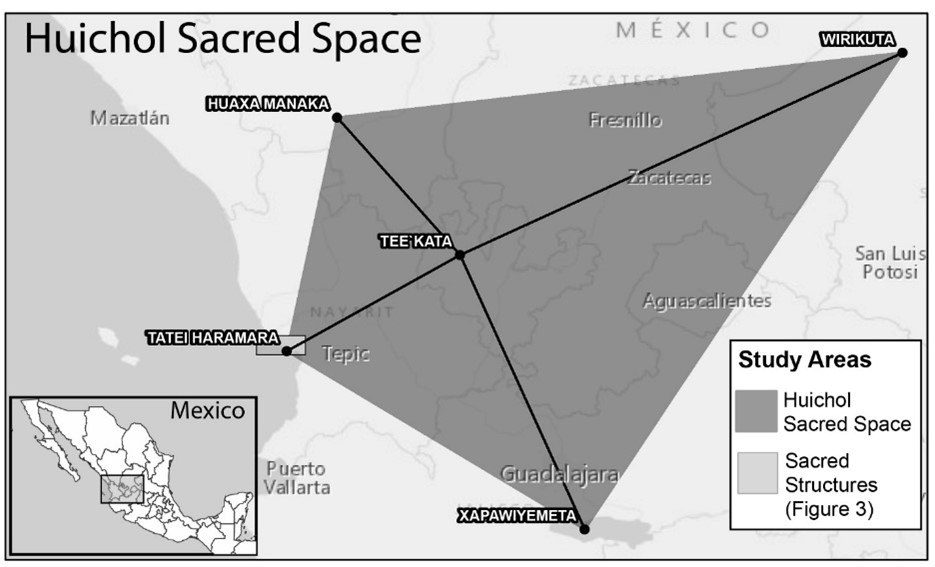

Geographical and environmental characteristics of the ancient Nayarit coast, as well as Aztec and colonial sources and modern carbon-dating technology, underscore the idea that well-organized human habitation on this part of the Nayarit coast existed long before conventionally constructed timelines suggest. The size and cultural development of Aztlán as a singular region remains purely speculative, but more than one origin myth from primary sources occupies, or claims, this same, very real, geographical space in northwestern Mexico. The most recent dates from 1113 A.D. with the migration of the Mexica/Chichimec out of Aztlán, while Huichol/Wixárika oral condition dates their beginnings through a “gateway” along this same coast perhaps a thousand years before that.

The Huichol/Wixárika[i] indigenous clans of the high sierras of Nayarit, Jalisco, and Zacatecas are one of the oldest and least culturally corrupted indigenous groups in Mexico. With their daily life centered around the sacredness of the deer, maize, and peyote, they are by now well-known and well-documented in the contemporary outside world (Arias 1899; Buron 2016; Neurath and Pacheco 2016). A popular internet video documents an annual sacred pilgrimage by Wixárika people to a sacred site fewer than five hundred meters offshore at San Blas to carry out rituals honoring their sea goddess, Tatei Hara Mara (Neurath and Pacheco 2016). This sacred rock is also considered the western boundary of the Wixárika world (Burton 2016). Wixárika shamans also visit an elephant-shaped rock about two miles north up and a mile off the coast. This large rock, a remnant of an ancient seafloor is locally known as The Elephant Rock, but shamans call it Venado Azul, meaning Blue Deer, or Guide. Isaac Murillo, San Blas native, historian, and museum curator, has spent several years in conversation with Wixárika shamans and other clansmen who come to the San Blas area annually to perform ceremonial rites at these two ancient and well-known sacred sites. He reports that the Wixárika believe that somewhere along this Nayarit shoreline is the door, or gateway, through which their ancestors/gods came into being. Supporting this idea is an article from 2000 in The American Journal of Human Biology, regarding Nei‘s genetic distancing, stating that “…The same analysis with grouped worldwide populations showed Native Americans as population closest to the Huichols, followed by Pacific Islanders and Asians (Villalobos Arámbula and Rivas, 2000). Perhaps Wixárika ancestors did come through a “gateway,” out of the Pacific, as coastal explorers from China, Peru, or the South Pacific, centuries before.[ii]

The question of whether or not indigenous origin narratives have any literal connection to actual geographical locations aside, the area around San Blas and Matanchen Bay has a psychic and spiritual association to a larger Mesoamerican historical/cultural tapestry than merely to its own local topography and inhabitants. The narratives and their regional associations exist in historical record and timeless traditional folklore and go back farther in time than the Aztatlan Complex era. These associations, together with the area’s extensive archeological record, underscore the possibility that the coastal region from Río Santiago to Zacualpán may have been a highly populated, socially well-organized center, a major cultural center, centuries before Sauer’s Aztatlan culture developed.

Mountjoy refers to his own findings associated with Middle Pre-classic (or Middle Formative epoch, 1000 B.C.-300 B.C.) occupation at San Blas. “The people who lived there terraced the hillside with impressive walls made of large boulders, and on the artificially flattened areas behind the terrace walls, they raised mounds of rock on which to build their houses…some dependence on domesticated plants…made some of their own grinding stones, pottery, net weights, nets, basketry, and jewelry” (Mountjoy 2000: 86). This evidence of Middle Formative settlement is scant, but it indicates the long existent presence of large populations with social organization and construction. Even the ancient food middens which Mountjoy and others have studied, 90 meters by 40 meters by four meters in depth, indicate “an ‘extractive facility’ linked to a more permanent Middle Formative village somewhere nearby” (Mountjoy and Claassen 2005: 208). And in a prior note Mountjoy states that “the coastline has been rising for a long time,” and that due to “the instability of the coastline, …Archaic deposits may have been either eroded or submerged” (Mountjoy 2000: 84).

Recent Discoveries

Recent discoveries in the San Blas area not only support the idea of significant Middle Formative epoch populations and social organization in this distinct region, but show evidence of sacred architecture and construction, or mound building, on a monumental scale with astronomical alignments to well-known indigenous sacred sites and with the summer solstice.

Since 2014, our team of Mexican and American historians and geographers has been exploring and examining two small hills (cerros, or cerritos) in northwestern Mexico in the municipality of San Blas. These structures have the symmetrical shape of, and have been referred to in local lore through generations as, pyramids. Wixárika shamans are frequently seen in the area by local agricultural workers who confirm the visits as traditional and generational, as history. Coincidental physical on-site evidence suggests this geographical space was altered or constructed space and that the surrounding region may have supported a large population and intense cultural activity long before the Aztatlan culture came to prominence.

In six different treks we have uncovered and documented what we believe to be evidence of human construction of these structures, including “unnaturally shaped” stone, etched stone, the on-site existence of different kinds of volcanic rock not normally found together, and places where the stone faces of these structures are clearly humanly marked and manipulated. Our most recent discoveries concerning spatial, geographical relationship of the tops of these cerritos to other known sites of archaeological significance (gone into more detail below) support our hypothesis that these structures are, indeed, of human construction, and not just a manipulation of the existing geography. So far, all exploration and investigation has been non-invasive, that is, involving no excavation or physical disturbance of the site, other than clearing the jungle cover.

Although these structures have been pointed out by local historians and noted by professional archeologists, no formal on-site investigation of these cerritos has been conducted until now. There are several reasons for this. First of all, most of the archaeological work done in this region has focused on the Aztatlan Cultural Complex. Its Late Era (circa 1300-1500 A.D.) evidence is relatively easily accessible to investigation along the northern Nayarit coast. Evidence of the Aztatlan Complex in its Late Era literally covers the surface of the ground all over this entire region. Small stone temples and ball court-shaped areas covered by a president-day tropical foliage are clearly visible to the naked eye, many gradually dismantled over hundreds of years by locals, much like Romans carted away parts of the Coliseum to build other things in other times and places. The Aztatlan culture was co-existent with, although geographically isolated from and less technically advanced than, the imperial states of the central plateau – Tenochtitlan, and Toltec empires. While evidence of the late Aztatlan Cultural Complex displays the general characteristics of all Mesoamerican cultures, its own Late Era pottery, metallurgy, and stonework were unique and are pale miniature imitations of those elements of culture refined and advanced over centuries in the central plateau (Mountjoy 1991). The structures we are examining are too big, too old, and too eroded, destroyed, and re-purposed in structure to fit into any concept of the Aztatlan Complex, and therefore, have not merited earlier, more intensive investigation. Secondly, the sheer size of these structures – perhaps as big as the Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon at Teotihuacan – with their steep, lower slopes presently cultivated as mango, banana, and lemon groves. and their tops covered in impenetrable, dangerous tropical jungle, has rendered them invisible and seemingly impossible as human constructs. They couldn’t possibly be man-built hills/cerritos/pyramids, man-moved boulder piled on man-moved boulder. And if they were from the Aztatlan culture, a mere fifteen hundred years old or so, even given the harsh environmental conditions of the tropical region, present-day destruction, and regional development, their remnants should be more obviously pyramidal than they are, at least to those thinking inside the historical and archaeological box. Wouldn’t they have been noticed and plundered by Nuño Guzmán during his annihilation of the region in the 1530s? These jungle-covered heaps probably seemed mere mountains even then. An American archaeologist doing some of the first excavations in the region in the 1970s posited that these cerritos were natural structures, but possibly man-shaped; they weren’t pyramids, however (Flores 2009). Subsequent archaeology has simply ignored them, but we believe the Aztatlan culture of the surrounding area is only the last patina overlying an older and well-advanced culture in this region. The structures we are exploring belong to this much older era.

[i] Known to the larger world as the Huichol, perhaps a derogatory mispronunciation by the Mexica, these indigenous clans call themselves “Wixárika” (“the people”) in their native tongue.

[ii] How and when earliest humans reached the west coast of the Americas is not the subject here. Much historical and archaeological evidence exists supporting this possibility. Monumental construction on the Peruvian coast has been dated to 30,000 years ago.

South cerrito/pyramid, 2014.

As Graeber and Wengrow point out in their ground-breaking study, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity”, that as early as the last Ice Age, “hunter-gatherer societies had evolved institutions to support major public works, projects, and monumental constructions, and thus had a complex social hierarchy prior to the adoption of farming.” (Graeber and Wengrow 2021:90) There is ample evidence to suggest such development happened on the Nayarit coast.

Thirdly, while prehistoric culture can only come to view by what is unearthed and interpreted, one of the acknowledged difficulties for regional archaeologists working on the Nayarit/Sinaloa coast from Matanchen Bay to the Culiacán River valley is the mutating nature of the coastal geography, not only by prehistorical alluvial erosion, but by modern agriculture development and social construction in the region (Gardaño Ambris 2015) as well. While contemporary development disturbs, injures, and hides archaeologically significant sites, it is the continuous geographical morphology over four thousand years that needs to be considered as an ongoing process that not only affected population fluctuations over time and determined the northward expansion and cultural community development of early Aztatlan; it also altered, perhaps buried, a longer-established cultural development in the region’s southern area. These ancient monumental mounds, perhaps ritually abandoned and deconstructed, environmentally eroded, and socially repurposed over three millennium, may be the only visible remaining clues to this older, buried culture. If these jungle-draped cerritos are finally proven to be human-built constructs, perhaps older than Olmec mound-building and stone carving on Mexico’s gulf coast, then contemporary concepts on the diasporas of people through Mesoamerican must be reshaped. We believe the legend/myth of Aztlán must be reconsidered as a geographical space altered by environmental and cultural forces over time and that the region may have been a source of human dispersion long before the Aztecs claimed it as their homeland.

The Geological Evidence

Given ancient volcanic activity in this region, some academics have proposed that these two cone-like structures may have been “natural” air or lava vents. In every one of six treks up, over, and around the two monumental structures, we have documented geological anomalies that indicate not volcanic action, but human manipulation of the structures’ slopes and the human shaping of stones found in situ.

Obvious examples of geological evidence left by humans consist of numerous sites where lava rocks distinctively different in texture, color, and hardness are piled/stacked together. Other large rocks have squared edges, and the surfaces of others are clearly etched. These signs are clear to anyone hiking the surfaces of the two cerritos, if they are searching with purpose, but there are no obvious “blocks” or parts of sculptures, or obvious “temples” to be found. We believe these structures were possibly torn down, ritually abandoned centuries ago, and any block-like remains re-purposed over the centuries. Such re-purposing has continued into the current century,[i] and what remains we have explored may be the cores of these ancient structures.

Furthermore, since slash and burn clearing has continued from the base to the tops of these structures, an eight-foot-wide hairpin track has been bulldozed up the north face of the north pyramid. Examination of that scar and the crosscut into the hill’s side shows its underlying makeup, not lava flows or boulders of basalt rock, but rock and dirt fill strategically shaping the generally smooth surfaces of these hills.

[i] According to Bill Wilson (Dec. 2016), former resident of the ancient village of Chacalilla, where only twenty years ago, he witnessed local villagers removing stone stairway blocks from the west side of a small, long-abandoned temple there identified by archaeologists as of the Late Era Aztatlan cultural complex.

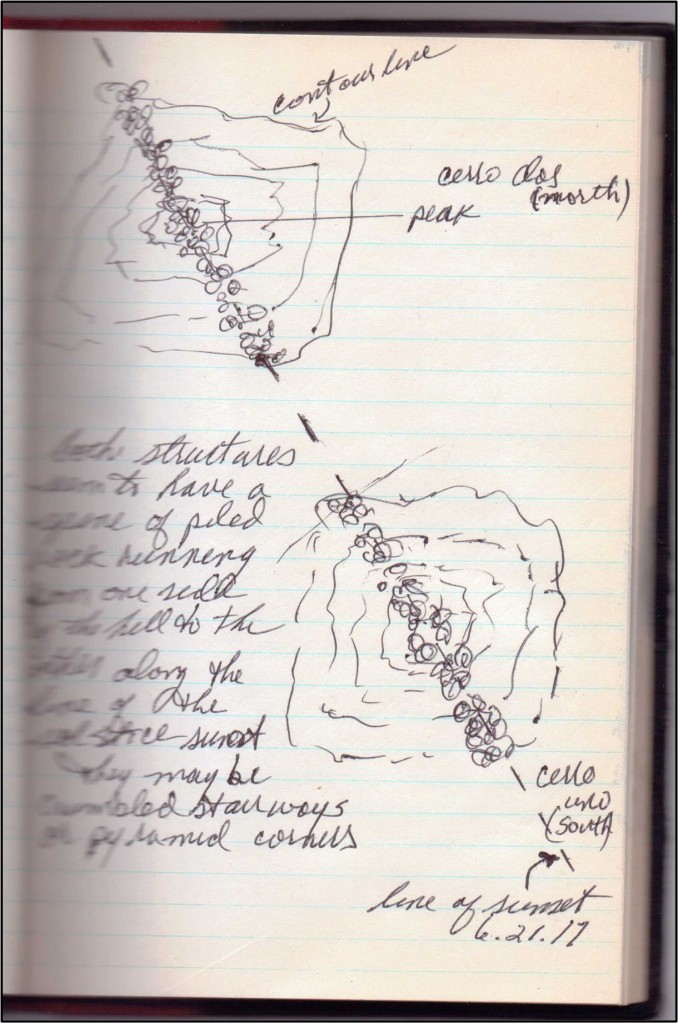

Composition of soil layers below surface of north face of north structure.

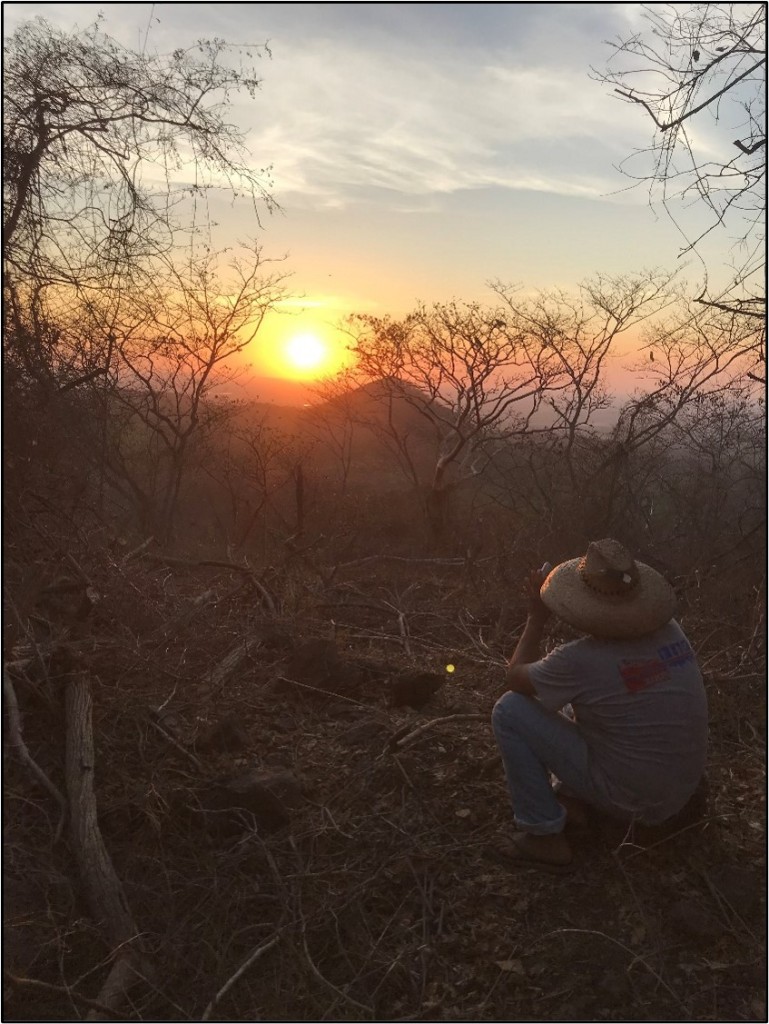

The best geological evidence took five treks to notice and the last to confirm, the area being so big and the jungle so overwhelming. Beginning at the southeastern base of the south structure and continuing up and over its top on a southeast to northwest trajectory, a distinctive ridge of rock rubble and boulders runs. The ridge disappears in jungle down the northwest slope and on a line with the top of the north structure. There are slight hints on the ridge on the north structure’s southeast slope, but during our Equinox trek on 21 March 2017, we had noticed how distinctive the line of boulders was at the top of this cerro and how it continued down the northwest slope. I made a fieldnote then to check this alignment on our 21 June 2017 Solstice trek to the top of the south cerro. This ridge seems to be like a spine that runs up and down the two pyramidal structures like a compass arm, and its trajectory meets the horizon where the sun sets on solstice.

The Spatial and Astronomical Evidence

While there is yet no absolute geological evidence that these structures are man-made pyramids, the spatial alignments of their summits to known indigenous sacred sites, along with clear astronomical alignments, cannot be regarded as natural to the environment or coincidental to the geography. Regardless of age, monolithic alignment construction is an indication of the level of population and cultural development achieved by their builders.

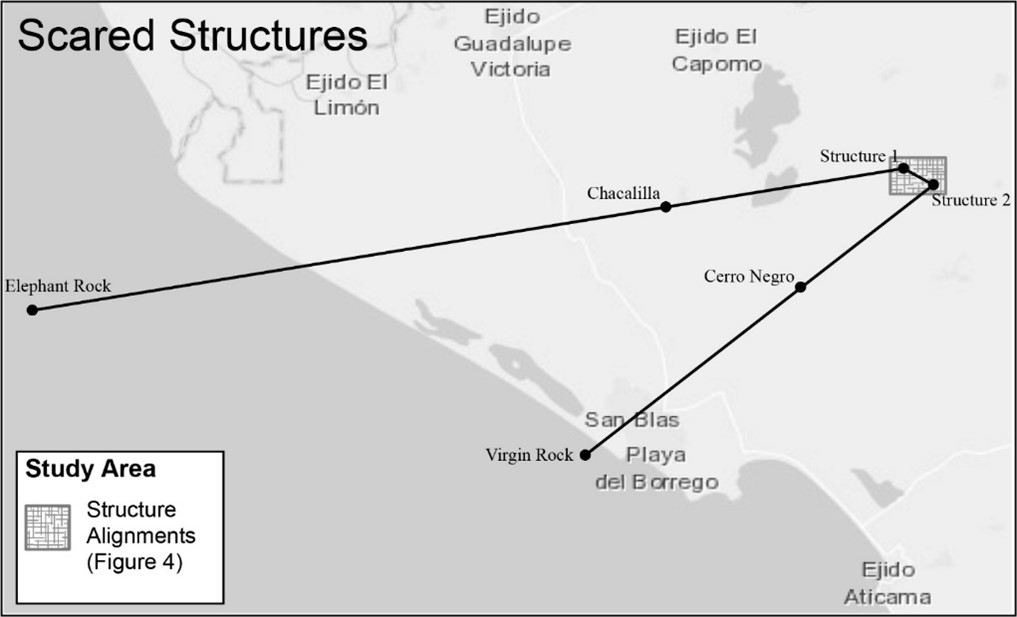

The first spatial alignment was noticed by Isaac Murillo, local San Blas historian, several years ago following interviews with Wixárika shamans and other clansmen who come to the San Blas area annually to perform ceremonial rites at the two well-known sacred sites, the Tatei Hara Mara (Rock of the Virgin) and The Blue Deer (Elephant Rock). While observing their ceremonies (performed in boats floating around The Blue Deer, Murillo noticed that the rock sat exactly on a line that passed through the hilltop above the village of Chacalilla, site of other pre-Aztatlan habitation, and met the top of the northern-most hill that everyone in the region calls a pyramid. We confirmed that alignment on 20 March 2017 from the north cerro top, looking WSW out to sea.

The extrapolation from there was simple: if there was one spatial alignment, might there be others? We obtained a contour map of the San Blas area from Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Geografía (INEGI), and plotted Murillo’s line from cerro top directly through the Chacalilla hilltop to Blue Deer out in the ocean. The next alignment we drew in was a direct line from the top of the southern cerro, directly through the peak of Cerro Los Negros (on whose slopes lay petroglyphs and other ruins) to the lighthouse hilltop on the west edge of San Blas, where the Wixárika shrine to Tatei Hara Mara sits in its grotto. If that line is extended eastward across Mexico, it passes directly through Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosí, another sacred Wixárika site considered to be the eastern-most point of what the Huichol consider their people’s sacred territory. This is the east/west axis of their world (Burton, 2013).

For Murillo, who has interviewed scores of Huichol pilgrims to San Blas, the association was an obvious one: This triangular opening with its view from the cerros west out to sea is the “doorway,” or “gateway” through which the Huichol ancestor/gods arrived, according to their origin lore. For him, these cerros are planned constructs, pyramids of significant religious purpose. Yet, there was still not enough evidence that leapt far enough beyond coincidence to refute academic skepticism. If the cerros were human constructs, religious in nature, then could there be solar or stellar relationships, particularly at equinox or solstice, as has proven the case throughout Mesoamerica through numerous eras?

That question led to the Equinox 2017 excursion, during which we made observations from the partially cleared top of the north cerro, hoping to see the sun set on March 20 in a direct line with the Blue Deer rock, Chacalilla’s hill, and our pyramid. But that alignment actually took place on 14 March, six days before equinox. After plotting the equinox sunset seen from the pyramid top on the INEGI map, further analysis showed that the Elephant Rock (Blue Deer), Chacalilla, cerro top alignment was nine degrees south of true west, and the sun sat nine degrees north of true west. Intriguing, but what, if anything, did it mean?

The only certain thing was that the sun would set on solstice 23.5 degrees farther north than at equinox, and from our line of sight on the north cerro an estimate of that angle seemed to bring the south cerro into line. The June 2017 excursion would confirm this conjecture. From the left shoulder of the south cerro, we photographed the sun setting on a trajectory that would make it drop behind the north cerro. With these structures so decayed and jungle covered, it was impossible to determine their exact tops or to get precise lines of vision, but the alignment of the sunset at solstice with the tops of these two hills/cerros/pyramids is too precise to be coincidental or natural to the environment. This alignment was confirmed again on summer solstice, 2019.

Photo shot from top of south pyramid toward the north pyramid, June 21, 2119.

No single piece of evidence reveals the presence of pyramids in Nayarit, but all the evidence taken together can’t be dismissed as merely coincidental or “natural” happenstance. Ancient man shaped his environment in this geographic locale, and it happened long before the Late Era Aztatlan Culture complex populated the region and spread north along the coast in the last years before The Conquest and Guzman’s holocaust.

Archeological examination is making it increasing clear that the coast of Nayarit was inhabited in the Early Formative period (2000 to 1200 B.C), perhaps continually, and the structures we have uncovered are another testament, not only to that earlier culture, but to its size and complexity as well. Name it what you will, it seems this culture inhabited this particular geographic space on Mexico’s west coast and predated the Aztatlan Cultural Complex by centuries. The problem of its evidential recovery or discovery is one of four thousand years of the geographic morphology of the Nayarit coastline, previously mentioned. The ancient watersf once may have come nearly to the bases of the structures we have explored. They would have been monuments at the ocean’s edge, or great lighthouses, visible a hundred miles at sea.

Conclusions

The extensive archeological record of the San Blas/Matanchen Bay area, with at least “five major archeological complexes” (Scott and Foster 2000: 134) and carbon-dating back to 2000 B.C. (Mountjoy, Taylor, Feldman 1972) , highlights the argument that the region deserves a fresh assessment as a major long-standing and continuously evolving cultural nexus on the Mesoamerican historical timeline, worthy of more focused exploration, anthropological study, and cultural preservation. Another major factor emphatically reinforcing this call is that

at least two different indigenous groups have origin narratives that connect directly, geographically, with this stretch of southern Nayarit coast, giving it a unique psychic and spiritual association to a larger Mesoamerican historical/cultural tapestry. And finally, new discoveries in the San Blas area not only support the idea of significant Middle Formative epoch populations and social organization in this distinct region, but show evidence of sacred architecture and construction, or mound building, on a monumental scale with astronomical alignments to well-known indigenous sacred sites and with the summer solstice.

If these jungle-draped cerritos are finally proven to be human-built structures, then the legend/myth of Aztlán must be reconsidered as a geographical space altered by environmental and cultural forces over time and that the region may have been a source of human dispersion long before the Aztecs claimed it as their homeland, and contemporary concepts on the chronology of development and the diasporas of peoples from this region through Mesoamerica must be reshaped.

There are literally hundreds of identified sites in Mexico awaiting archeological exploration, but discovering pyramidal remains in northwestern Mexico, in Nayarit and dating from before the Aztatlan Cultural Complex, would have profound implications. We believe that our geographical investigation presents enough evidence of the possibility to warrant more intense professional examination. Specifically, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) used in precise locations around these structures would help determine the presence of caves at this site, and caves are a major factor in all aspects of Mesoamerican lore and codices (Shávelzon 2015). Using light imaging radar (LIDAR) over a forty square kilometer area around these structures would reveal as yet unknown trails and ancient dwelling centers (which we confirmed in our own explorations) that may show this region to have been far more populated and far earlier than previously believed.

References

Arias de Sabedra, Antonio (1899) Información rendida por el P. Antonio Arias y Saavedra, acerca del estado de la sierra del Nayarit, en el siglo XVII. In Nayarit: Colección de documentos inéditos, históricos y et nográficos, acerca de la sierra de ese nombre, edited by Alberto Santoscoy,. Guadalajara.

Beekman, C.S. (2010) Recent Research in Western Mexican Archaeology, Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 18, No. 1 (March), pp. 41-109.

Beekman, C.S. and Alexander F. Christensen. (2003) Controlling for Doubt and Uncertainty through Multiple Lines of Evidence: A New Look at the Mesoamerican Nahua Migrations.

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Jun., 2003), pp. 111-164.

Burton, T. The sacred geography of Mexico’s Huichol Indians, GEO-Mexico, the geography and dynamics of Modern Mexico. http://geo-mexico.com/?p=8547. Last accessed 12/17/18.

Campos Moreno, Araceli. (2016) Maravillas y prodigios en la crónica de fray Antonio Tello, Revista De Literaturas Populares XVI -1 y 2.

Cartografía Histórico de la Nueva Galicia. (1984) University of Guadalajara: Guadalajara.

Duran, Fray Diego. (1880) Las Historia de las Indias de la Nueva España y Islas de Tierra Firme. Imprente de Ignacio Escalante, Mexico.

Foster, M. S., and Gorenstein, S. (eds. (2000) Greater Mesoamerica: The Archaeology of West and Northwest Mexico, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Garduño Ambriz, M. (2015) San Felipe Aztatlán: Arqueología de rescate en la zona nuclear costera Aztatlán. In Revista Occidente, June 2015. http://www.mna.inah.gob.mx/contexto.html

Graeber, David and Wengrow, David. (2021) The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux: New York.

Leven Rojo, Danna A. (2014) Return to Aztlan: Indian, Spaniard, and the Invention of Nuevo Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman.

Martinez Martinez, Rubi E., Rodolfo Silva, and Edgar Mendoza. (2014) Identification of Coastal Erosion Causes in Matanchen Bay, San Blas, Nayarit, Journal of Coastal Research, SI No. 71. (Allen Press Publishing: Coastal Creek, FL).

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo.( 1990) “Las Aztecas.” La Aventura Humana Mexico: Barcelona.

Meighan, C. W. (1974) Prehistory of West Mexico. Science, New Series, Vol. 184, No. 4143 (Jun. 21, 1974), pp. 1254-1261.

Mountjoy, J. B. (1971) A Dated Cruciform Artifact. The Kiva, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 42-46. Made available courtesy of AltaMira Press: http://www.altamirapress.com/RLA/Journals/Kiva/Index.shtml

___ (1987) Antiquity, Interpretation, and Stylistic Evolution of Petroglyphs in West Mexico American Antiquity, Vol. 52, No. 1 (Jan., 1987), pp. 161-174.

___(1991) West Mexican Stelae from Jalisco and Nayarit. Ancient Mesoamerica, Vol. 2,

pp. 21-33. Cambridge University Press.

___(2000) Prehispanic cultural development along the southern coast of West Mexico. In Foster, M. S., and Gorenstein, S. (eds.), Greater Mesoamerica: The Archaeology of West and Northwest Mexico, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, pp. 81-106.

___(2015) La Colonización Del Lejano Occidente de México Por Agricultores Sedentarios Durante El Formativo Medio, 1200 a 400 a.C. V. In Revista Occidente, June 2015. http://www.mna.inah.gob.mx/contexto.html.

Mountjoy, J. B., and Claassen, C. P. (2005) Middle Formative Diet and Seasonality on the Central Coast Of Nayarit, Mexico. In Dillon, B. D., and Boston, M. A. (eds.), Archaeology without Limits: Papers in Honor of Clement W. Meighan, Labyrinthos, Lancaster, CA, pp. 267.

Mountjoy, Joseph B., R.E. Taylor, Lawrence H. Feldman. (1972) Matanchen Complex: New Radio Carbon Dates on Early Coastal Adaptation in West Mexico, Science, Vol 175. No. 4027 (Mar. 17,). American Asso. for the Advancement of Science. pg. 1242-1243.

Navarrete, Federico. The Path from Aztlan to Mexico: On Visual Narration in Mesoamerican Codices, (Spring 2000) RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 37, pp. 31-48.

Neurath, Johannes and Ricardo Claudio Pacheco Bribiesca. (2010) Pueblos Indígenas De México Y Agua: Huicholes (Wixarika), Atlas De Culturas Del Agua En América Latina Y El Caribe. Instituto Nacional De Antropología E Historia. Accessed 10/25/18 at https://www.academia.edu/8476367/ATLAS_DE_CULTURAS_DEL_AGUA_EN_AM%C31889RICA_LATINA_Y_EL_CARIBE_PUEBLOS_IND%C3%8DGENAS_DE_M%C3%89XICO_Y_AGUA_HUICHOLES_WIXARIKA

Ortíz García, Elena. (1997) Los Códices Cartográfico-Históricos. La Historia Tolteco-Chichimeca, EHSEA. N° 14/Enero-Junio 1997, pp. 301-323.

Sauer, Carol 0., and D.D. Brand (1932) Aztatlan: Prehistoric Mexican Frontier on the Pacific Coast. Ibero-Americana 1. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Schávelzon, Daniel. (1978) Temples, Caves, or Monsters? Notes on Zoomorphic Façades in Pre-Hispanic Architecture, Third Palenque Round Table. University of Texas Press, Austin and London: Austin, Texas,. Pgs. 151-162. Accessed on 30 March 2015 at www.danielschavelzon.com.ar

Smith, Michael. (1984) The Aztlan Migrations of the Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History? Ethnohistory, Vol. 31:3, pp.153-186

Stott, Stuart D. y Michael S. Foster. (2000) The Prehistory of Mexico’s Northwest Coast: A View from the Marismas Nacionales of Sinaloa and Nayarit, in Foster, Michael S. and Shirley Gorenstein, Greater Mesoamerica: The Archaeology of West and Northwest Mexico, pp. 107-135. University of Utah Press. Salt Lake City.

Tello, Antonio. (1891) Crónica miscelánea en que se data de la conquista espiritual y temporal de la Santa Provincia de Xalisco en el Nuevo Reino de Galicia y Vizcaya y descubrimientos de Nuevo México. Imprenta La República Literaria, Guadalajara. .

Williams, E. (2004). El Occidente de Mexico: un area cultural Mesoamericana, online article published at http://www.famsi.org/spanishyresearch/williams/ “Prehispanic West México: A Mesoamerican Culture Area,” Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. http://www.famsi.org/index.html